On Photographic Theory - A Brief Intro to the Theory of Image

Chapter 1

“The goal is not to make something factually impeccable, but seamlessly persuasive.” – John Szarkowski

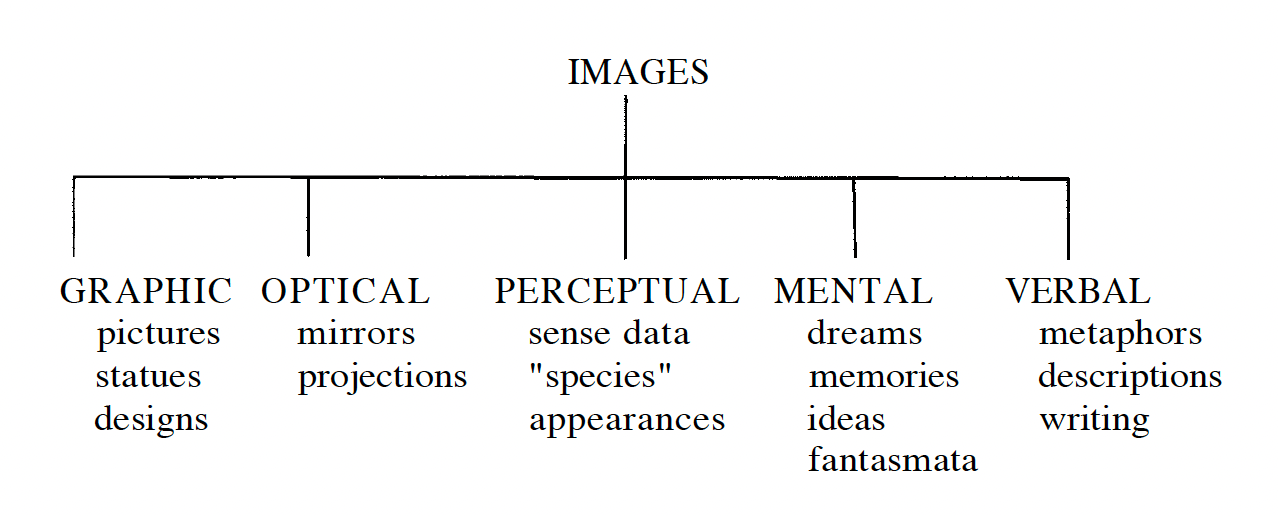

The act of describing in and of itself is often an arduous ordeal more than we perceive it to be. The act of finding adjectives and stringing them together to describe something that “exists”, especially at a moment’s notice forces the brain to rack its mental dictionary and grasp for not just the most proper word, but the most descriptive word. People such as Haruki Murakami, George Orwell, Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Rumi have been made famous by their use of description. Hence terms such as “Orwellian” and so on. Perhaps the issue that I have with “description” is that in almost any scenario in which somebody is forced to “describe”, they are left describing an “image”. Usually something of the graphic or optical type. On occasion people can describe thoughts or words, as this is especially seen in psychotherapeutic endeavors, although this often turns into an adventure of mental imagery, where ideas such as dreams and the human senses come into play1. Describing one’s feelings, whether it being love, sorrow, happiness, melancholy, etc. is probably at the summit of the theoretical mountain that “description” is. This problem is one that is relatively common for anyone that works in a field relating to graphics. A photograph, as in graphic imagery, and text, as in verbal imagery, seem to be in a never-ending waltz that has no resolve. But in order to understand “image” and “description” it would be a good idea to refer to the sort of genealogy of imagery that W.J.T. Mitchell proposed in 1984.2

Figure 1.1 Mitchell’s proposed genealogy of image.

This graphic is one that has been permanently impressed into my mind. As “image” and what it can and cannot be is delineated from the graph. This graph also shows that the idea of image is far broader than most people would believe it to be. Image can be photographs, dreams, spoken word, written words, the senses and so on. In literary critique we can see inclusion of mental in such works as Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s famous One Hundred Years of Solitude, and other, especially Latin American writers, for their use of magical realism in their works. Descriptions of people, places and things that take fantastical and often otherworldly qualities. These qualities can similarly be found in pictures as well, although they can be difficult to articulate. But it is also in this graph that I further elaborate on my original problem of graphic image and verbal image.

Whether it is purposeful or just a coincidence, graphic pictures and verbal writing are quite literally on polar opposite ends of the genealogy.3 I find this polarization most interesting, especially since pictograms and hieroglyphics served the purposed of “writing” many millennia ago and many centuries before proper scripts had been created. Image in the graphic form is the very origin of written communication. Petroglyphs can be found on every continent worldwide and were used by a plethora cultures from the Jicarilla Apache in New Mexico, tribes in Western Africa and early Iranian cultures on the lower plains of Central Anatolia to name only a few.4 The ancient world obviously had the opposite problem that we have today, for early proto-cultures spread around the world used the pictorial image as the sole means of written communication until the development of the first proto-scripts in the Levant around the 13th century BC. A few languages, such as Chinese, continue to use a logographic script to this today, although it is obviously far more advanced and refined than its early predecessor.5

Logographic scripts could also be problematic in their function as well. Hieroglyphs are difficult to translate and decipher without some sort of key to properly decipher them, especially those ancient scripts that have been extinct for millennia.6 In scenarios where it is impossible to decode the hieroglyphics, their meanings can become infinitely abstract. It is often through luck alone that we are able to find ancient transcriptions such as the Rosetta Stone that allow us to decipher ancient logographic scripts. Some languages such as Greek and Hebrew can help us to decipher these ancient scripts, as there were often dual usages of these scripts, especially in the area around the Mediterranean, although neither of these scripts in their modern forms can remotely be considered logographic. A hieroglyph of a cow for instance could mean any variety of ideas ranging from a pure definition of “cow” to more abstract ideas such as “value”. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein attacks this problem head on by directly addressing the meaning of “word”. As he points early in his “Blue Book”, that words and vision are always intrinsically entwined.7 When we mention a word like “pencil”, we are using the English language mind can image a variety of things, the color yellow, a pink eraser, the hexagonal shape of the pencil’s shaft. To the Polish language mind will probably imagine the ołówek as something similar in shape, description, and order, but what happens when something is seemingly non-existent in another language? Wittgenstein uses the example of presenting a banjo to a German speaker and forcing them to figure out what it is. They will probably mislabel it as a guitar, even though it is most definitely not a guitar, because such visualization, object, and word does not exist in German to describe the English banjo.

But this also begs the question if graphic and verbal should be more closely tied together in the first place, or if this is a cosmological accident of sorts for the human mind?8 This problem of polarity with the caption or description of a photograph is one that haunts everyone from the photographer to editors, journalists, designers and even observers of the work. The matter of fact is that the visual plane rest on the photograph itself, and not in the three-dimensional of the mind of the observer. This change of visual forces a change in description. But problematically enough for the photographer, they are often the one burdened with creating the caption to begin with. Alec Soth, the Minneapolis based photographer outlines this issue on a broad level in his YouTube video titled “Pictures & Words #1”.9

Wittgenstein partly approaches this by addressing visual understandings of the mind. The mind can visualize color, smell, taste, sensations, and so on. But grouping mental visualization into the same realm as pure visual imagery may be problematic, especially if the mind has very few visual or sensory prompts to be able to fluidly create the image in the mind.10 As Mitchell states in relation to Wittgenstein’s work, there is a barrier between mental and physical images that is drawn mentally. We often assign different realms for different sense, often without realizing that they all meld over each other in a messy and unpredictable way.

Furthermore, Soth describes the balance of image to word as like having a set of scales. Too many words and you encumber the photo with so much context that the photo loses meaning and is merely accessory to the text.11 Yet a photo itself rarely holds true understandable meaning. It holds visual understanding of a thing, person, place and so on. Visualization at its purest form is simply an exercise of the consciousness. There will always be context that is needed to grasp the photographs meaning beyond strict visualization. This problem is occasionally solved by simply leaving the photograph untitled. Yet leaving a photo untitled does not leave the piece without context.12 If it is published concurrently with a larger body of work whether it is a book, news article, or magazine, there is almost always a title and maybe even a foreword or article to the broader work that it is a part of.

This is not to say either that it is a sort of cheap escape to not assign words to a photograph. As Stephen Shore recounts in his memoir, Modern Instances, William Eggleston was invited with a few other photographers to talk at a lecture about their works in Venice in 1987. When Eggleston was asked about his work he simply replied, “I think I’ll just show my work and not say anything.”.13 This shibboleth of sorts is one that every creative wishes they could attain to a certain degree. As Soth says in his video, “A part of me would just love to avoid it all together and live in a utopic place in which I only make pictures and they speak for themselves, but utopias don’t exist.”.

It is also of equal importance to decide how the image will be presented to the audience. The presentation is often just as important as the execution of the image itself. In our current digital era small cellular phones and computer screens have become the primary form of visual observation. With image reduced to small screens, the way that we use and produce images of all types is massively changed. Just 40 years ago vinyl records were the primary form of owning music. A large, plastic disc with limited sonic capacity would lead to people owning large collections of music, displayed on bookshelves like textual works. Since the digital revolution audio and spoken images have evolved to being stored as data, with different file types, bitrates, and modes of transmission from the device to the ear. Stored as an mp3, FLAC, or streamed from the device wirelessly. Is the spectator using wired headphones, wireless headphones, a sound system, or car speakers? This same exact conundrum can be seen with visual image as well. Is the observer viewing the image on a cell phone, laptop, television screen, billboard, or as a physically printed copy? Even the method of the printed copy has totally changed as copies handmade in a darkroom are far more uncommon than the digital inkjet print. But this is not a classic post-modernist argument of digital versus analog formats, as both are forced to coexist today, but it is an argument questioning how the different formats may have a different and possibly catastrophically outsized effect on a human being’s perception of a piece.

Perhaps it is essential to ask the question of what sort of consequences do these theories and ideas of image vs text hold for the average spectator of such instances. It is also important to remember that we are all spectators of this constant conundrum as well, any person that reads a newspaper, looks at an advertisement on public transit, or reads a restaurant menu, will always be subjugated to the constant balance of text and picture. Consequently spectators are perhaps the most vulnerable group to this predicament as they eventually become victimized or blessed to a well balanced description for a picture. If a description is terribly inaccurate or incorrect then the spectator is now subject to the toil of confusion or disinformation. But this is also the most problematic downstream effect that description can cause on a societal level, and its current ramifications in this digital age have become staggering.14 This is also an issue for everyone going upstream as well. From the editor to the writer to the publisher and eventually the photographer, the textually related meaning of the photograph must be preserved, yet issues such as spelling errors, mistranslations, disorganization, and poor-quality control can all easily skew the textual description given to a photo.

Marshall, Julia. “Image as Insight: Visual Images in Practice-Based Research”, Studies in Art Education, Fall 2007, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 23-41.

Mitchell, W.J.T., “What Is an Image?”, New Literary Historian, 1984.

Ibid. Mitchell

Dinçol, Ali, & Dinçol, Belkis, & Peker, Hasan, An Anatolia Hieroglyphic Cylinder Seal from the Hilani at Karkemish. Orientalia, NOVA SERIES, Vol. 83, No. 2, pp. 162-165, 2014.

Chao, Yuen Ren. A Note on an Early Logographic Theory of Chinese Writing. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Jun 1940, Vol. 5, No. 2.

Serruys, Paul L.-M., Studies in the Language of the Shang Oracle Inscriptions, T’oung Pao, Brill, Second Series, Vol. 60, Livr, 1/3, 1974.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Blue Book, Wittgenstein Archives, University of Bergen, https://www.wittgensteinproject.org/w/index.php?title=Blue_Book.

Ibid. Mitchell.

Soth, Alec. Pictures & Words #1. Retrieved January 14, 2023, from 2021.

Ibid. Wittgenstein. Blue Book.

Ibid. Soth.

Ibid. Soth.

Shore, Stephen. Modern Instances, the Craft of Photography. Mack, London, 2022.